Two Studio Ghibli classics are turning thirty this year. One is Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro, and the other is Isao Takahata’s devastating Grave of the Fireflies. We initially planned to rerun this article in celebration of this anniversary. Sadly, we are also now honoring the iconic Takahata, who passed away on April 5th at age 82. In addition to mentoring the younger Miyazaki and co-founding Ghibli, Takahata produced all-time classics of Japanese cinema, pushing animation in new directions, and working tirelessly to perfect new forms. From Only Yesterday to Pom Poko to the stunning Tale of Princess Kaguya, all of his films deserve your attention.

But now we return to the studio’s seemingly strange choice to premiere My Neighbor Totoro and Grave of the Fireflies as a double feature in Japan. (I do not recommend recreating this experience!) Together, three decades ago, Miyazaki and Takahata gave us a new childhood icon, and an indelible portrait of the true cost of war.

Calling it a whiplash-inducing emotional rollercoaster is a bit of an understatement…

Historical Background

Studio Ghibli was officially founded after the success of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Its first film was an original creation of Hayao Miyazaki’s, Castle in the Sky. A few years after that film, Miyazaki and his friend and collaborator, Isao Takahata, decided they would each tackle a film to be released in the same year. Miyazaki was not yet the animation god that he is now, so when he told people that his next movie would be a highly personal, almost drama-free work about two little girls and forest spirit, bottom-line-minded business men didn’t see the appeal. Meanwhile, Takahata wanted to adapt a bleak short story: Akiyuki Nosaka’s Naoki Prize-winning Grave of the Fireflies, written in 1967.

Grave of the Fireflies follows a young brother and sister fighting for survival in Japan during the last months of World War II. It’s based on Nosaka’s own tragic childhood, particularly on the deaths of his two sisters, both of whom died of malnutrition during the war. The second sister died after their father’s death in the 1945 Kobe bombing left Nosaka her sole caretaker, and he wrote the story years later to try to cope with the guilt he felt. Takahata wanted to tackle the story as an animated film because he didn’t think live-action could work – where would a director find a four-year-old who could convincingly starve to death on camera? But Takahata thought it would make for a dramatic feature, one that would show the young studio’s range. There was also a connection to Takahata’s childhood that I’ll detail below.

Totoro also came from his creator’s childhood: Miyazaki would draw a rotund bear/cat hybrid as a boy, and in the 1970s began drawing the adventures of a young princess who lives in the woods with a similar, slightly-less-cuddly, beast. That princess was eventually divided into two characters—one version of the princess became even more feral, and evolved into Mononoke Hime, but the other became a six-year-old girl who met a softer version of Totoro—and who was later again divided into the characters of Mei and Satsuki as they appear in the finished film.

Miyazaki set the film in Tokorozawa City in Saitama Prefecture, which had once been lush farmland, but in the late 1980s was being swallowed by the sprawl of Tokyo. He set out to make a film about childhood innocence, where the only antagonist—the mother’s illness—was already being defeated, and where neighbors—whether human or forest god—took care of each other. The problem was that studio execs weren’t sure that a film about innocence, starring a big furry god that their director had just made up, would set the box office on fire.

Toshio Suzuki, the not-nearly-sung-enough genius producer, was the one who suggested a way to fund both of their films projects: Shinchosha, the publisher of Grave of the Fireflies wanted to break into the movie business. Perhaps they’d pay for a double bill? This would allow Takahata to adapt the story into a faithful, feature-length film without having to deal with the difficulties of live action, and Miyazaki would have backing to make his whimsical forest spirit movie. Plus, they argued that teachers would likely arrange school outings to show their charges the historically significant Grave of the Fireflies, thus guaranteeing that the double bill would have an audience.

This worked…to a point. The films were made and released together, but the studio quickly found that if they showed Totoro first, people fled from the sadness of Fireflies. Even swapping the films didn’t exactly result in a hit. It was only two years later that Studio Ghibli became the iconic studio we know, thanks to a merchandising decision that ensured their success.

The films are both masterpieces of economy, and creating extraordinary emotional tapestries out of tiny details. I rewatched the two films in the correct double feature order to try to recreate the experience of those poor unsuspecting Japanese audiences of 1988.

Grave of the Fireflies, or, Abandon All Hope

I should start by mentioning that I swore a blood oath to myself that I would never watch Grave of the Fireflies again.

I watched it again for this post.

I started crying before the opening credits.

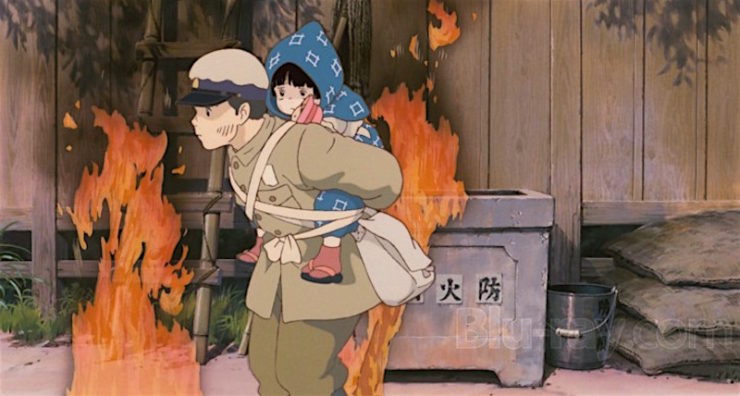

Now, I don’t cry. I know people who sob over movies, books, PMS, sports, The Iron Giant… I am not such a person. But this movie opens with the death of a child, and gets worse from there. So in all seriousness, and all hyperbole aside, the following paragraphs and images are going to be about the death of children, so please skip down to the Totoro synopsis if you need to. I’ll be talking about Grave again further down, and I’ll warn you there, too. In the meantime, here’s a gif of older brother Seita trying to amuse little sister Setsuko after their mother is injured in an air raid:

Spoiler alert: it doesn’t work.

Isao Takahata has never been lauded to the same extent as his colleague Miyazaki. He joined Toei Animation right out of university, and worked on television throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. He began working with Miyazaki on his feature directorial debut, Hols, Prince of the Sun, in 1968, but when the film underperformed he ended up back in TV. He and Miyazaki teamed up for an adaptation of Pippi Longstocking that never got off the ground, and for a successful series titled Heidi, Girl of the Alps. He came aboard Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind as a producer, and then produced Studio Ghibli first feature, Castle in the Sky, before tackling what was only his second feature-length animation as a director, Grave of the Fireflies.

Takahata’s attachment to Grave stemmed largely from the events of his own childhood; as a nine-year-old boy, the future director lived through the horrific bombing of Okayama City, and drew on his own experience for the film. He and his ten-year-old sister were separated from the rest of their family, and fled through the city as it burned. “As I was running, more and more all around me, something would get hit, so the running would get more and more confusing. I’ll go this way, I’ll go that way, and then something was bursting into flames all around… there were places where they kept water to put out fires, and you’d pour it on yourself. But it would dry instantly. So what were we to do?” The two managed to reach the river, but along the way Takahata’s sister was wounded in an explosion, and Takahata’s feet were punctured by glass and asphalt that were melting in the heat.

This experience shows through in Grave, as the film’s early air raid sequence is one of the most harrowing events I’ve ever seen in on screen. In the last months of World War II, Seita and his little sister, Setsuko, are living an uncomfortable but manageable life with their mother. Seita believes the Japanese fleet is unstoppable, and his father is an Army Captain, so the family gets a decent ration of food and benefits from the military. This changes in an instant, however, when the children’s mother is grievously injured during an air raid. She dies from her wounds, but not before we get to see this:

Seita spends the next few months trying his best to care for Setsuko, always assuming that his father will be coming home. First, the two children go to live with a horrible abusive aunt, who starts off playing nice because she—like all the characters—thinks that Japan will win, and that the military will come home and those who supported them will be showered with rewards. As the weeks roll on, however, and Seita continues writing unanswered letters to his father, the money dries up, and so does the aunt’s tolerance. She begins needling Seita for going to the bomb shelter with the women and children, and for not working, despite the fact that there aren’t any jobs for him.

Seita finally decides to move into a lakeside bomb shelter with Setsuko. On paper this seems like a terrible decision, but Takahata uses perfectly escalating moments with the aunt to show just how bad life has become, until their escape to the shelter comes as a glorious relief. This makes it all the worse when the knife twists a few scenes later: Japan has begun to lose the war. Seita has money in the bank from his mother’s account, but no one is taking yen, and the kids have nothing to barter. He starts looting during air raids, but that means putting himself at risk, and leaving poor Setsuko alone for hours at a time. Finally he begins stealing. Throughout all of this Setsuko gets skinnier and skinnier, and breaks out in a rash.

No adults help. At all. Everyone is too concerned with their own survival. The one glimmer of “hope” comes when Seita is caught and beaten for stealing—the police officer takes his side and threatens to charge his captor with assault. But even here, the cop doesn’t take Seita home, or give him any food. Finally Seita goes into town, and is able to buy food, but while he’s there he learns that the Japanese have surrendered, and that the fleet has been lost. His father is dead. He and Setsuko are orphans.

But wait, there’s more!

He arrives home, and finds his sister hallucinating from hunger. He’s able to feed her a piece of watermelon, but she dies later that day. The film doesn’t specify how long Seita survives after that, but it seems like he’s given up. He spends the last of his mother’s money on Setsuko’s cremation, and finally dies at a train station just as the U.S. occupying forces are arriving.

So.

The one lighter element here is the film’s wraparound narrative. The movie opens with a child dying—Seita’s collapse in the train station. His body is found by a janitor, who also notices that he’s clutching a canister of fruit drop candy. In a genuinely weird touch, the janitor opts to throw the canister out into a field, by using a perfect baseball player’s wind-up and pitch motion. Is this a nod to the encroaching American culture? Because it creates a horrific jarring, callous moment. A child has died alone and unloved, but life is going on, this janitor is a baseball fan, and America is at the doorstep. As soon as the canister lands, Setsuko’s spirit comes out of it, and waits for her brother. He joins her a moment later, and the two travel together on the train (the normal Japanese subway, not like a spectral train or anything) and they go to a lovely hill above Kobe. The film checks in with the spirits a few times, and closes on them sitting together on a bench, watching over the city.

Again, the brightest spot in the film is the fact that you get to see the kids as happy-ish ghosts. Earlier, the sequence of their move into the bomb shelter is disarmingly lighthearted, at least at first. The kids catch fireflies and set them loose in their bedroom as lights, but of course by morning the insects have all died. When they reunite as spirits they’re surrounded by clouds of fireflies again—but are these living insects, lighting the ghosts’ way? Or are these spirits, too?

But even these fleeting moments of joy are brought back down by the ending. Seita and Setsuko have been reunited, and seemingly have an infinite supply of fruit candy to share, but they’re also doomed to sit on their bench watching life unfold without them. This creates an extraordinary feeling of weight. Like all modern countries, Japan’s glittering present was built on the bones of its wartime dead. The prosperous country that Takahata lived in, and the industry he worked in, both sprang from a post-war economy, with the loss of war forever hanging in the background.

As an American who was raised by her Dad to watch WWII-era classics, watching this movie a decade ago was my first time seeing an entirely Japanese perspective on the war. (I did have a mild Empire of the Sun obsession back in middle school, but even there, while Japanese culture is respected, the British and American POWs are clearly the heroes of the film.) And while I knew the statistics on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it was still eye-opening to see Japanese civilians gunned down by fighter pilots, towns set on fire, children slowly starving to death from a lack of resources. While Takahata has said that he doesn’t intend the film to be “anti-war” it’s impossible to watch it and not see that whatever the ideologies at stake, it’s innocent children who suffer.

So in the name of innocent children, I’m going to move on to Totoro now, OK? I do think Grave of the Fireflies is an extraordinary achievement, and I think people should probably try to watch it once. I think it should be used to Ludovico world leaders before they authorize acts of war. But I also don’t like dwelling on it.

My Neighbor Totoro, or, Picking Up the Tattered Remains of Hope and Wrapping Them Around You Like a Warm Blanket On a Cold, Rainy Afternoon.

My Neighbor Totoro is set in the late 1950s, in an idyllic version of Miyazaki’s neighborhood. It’s possible that this film, like Kiki’s Delivery Service, takes place in a timeline where WWII was averted—if not, it’s barely a decade after the sad deaths of the children in Grave of the Fireflies, but it might as well be a different world. Here the sun shines, people live in quiet balance with nature, neighbors check in on each other, and elderly ladies happily care for a stranger’s children.

Satsuki and Mei Kusakabe move out to the country with their university professor father in order to be closer to their mother, who’s in the hospital with an unnamed illness. (She probably has tuberculosis—Miyazaki’s mother fought tuberculosis for years during the director’s childhood.) When we see her she seems OK—weak, but recovering. Both parents are loving and understanding, the neighbors are welcoming, and Nature, as we soon learn, is actively benevolent. This is that rare jewel—a story with no villain, no needless cruelty, and only a tiny hint of conflict.

The kids spend moving day rushing from room to room screaming with joy at literally everything they see. The meet Nanny, the elderly next-door neighbor, and chase Susuwatari—wandering soot or soot sprites (endearingly dubbed as “soot gremlins” in some versions of the film)—that have moved in since the house was empty. And here’s our introduction to the film’s philosophy: the kids see the soot sprites. They tell their father. Nanny and their father completely and unquestioningly accept the soot sprites’ existence. From here on we’re in a world with magic creeping in at the edges, in much the same way that the abject horror of GOTF crept in gradually, here a sort of healing magic seeps into the children’s lives. They’ve had a rough year. Their mother being hospitalized with an illness that’s often terminal, their father picking up the slack at work and at home, a move, and for Satsuki, an abrupt push from being Mei’s sister to being her caretaker. But here in the country, they’re surrounded by people who love them immediately, including the king of the forest.

Mei finds the small Totoro and pursues him into the forest. Like Alice before her, she falls down a hole, and finds herself in a strange world. Not a wonderland, however, simply the Totoro’s den. Everything about this scene is designed to feel safe. The snoring, the squishiness of the Totoro’s stomach, the whiskers, the button nose—you can feel his warmth radiating through the screen. OF COURSE Mei climbs up and falls asleep on him. OF COURSE he doesn’t mind. Like an old nanny dog who sits patiently while a baby tugs her ears, Totoro understands that the small loud pink thing means well.

And while this is a very sweet child’s story, where the film vaults into all-time classic status is when Mei tells Satsuki and her dad about Totoro. They think she’s dreamed him at first, and she gets upset. She thinks they’re accusing her of lying. And Miyazaki, being a filmic miracle worker, stops the film dead in order to let Mei’s anger and feeling of betrayal settle over everyone. This isn’t a film for grown-ups who can laugh away a child’s emotions, or wave their reactions away as tantrums or silliness. Mei is four years old, and she’s just told the people she loves most about an amazing adventure, and they don’t believe her. This is a tragedy. Maybe even a more concrete tragedy than her mother’s nebulous illness. And because Miyazaki is creating the world as it should be, Professor Kusakabe and Satsuki realize they’ve messed up.

They both reassure Mei that they believe her, and follow her to the base of the camphor tree that hides Totoro’s den. There’s a shrine there, and Professor Kusakabe leads the kids in bowing and honoring the gods of the shrine. This is the correct way to interact with Nature. Mei has been given a great gift—a direct encounter with the King of the Forest—and rather than ignoring the gift, or assuming it’s a hallucination, Professor Kusakabe makes this a special and solemn moment for the kids…and then races them back to the house for lunch, because kids can only stand so much solemnity. This becomes an ongoing theme in the film. My Neighbor Totoro would probably not be considered a “religious” children’s film in the Western sense the way, say, The Prince of Egypt would be. But Totoro is a forest god, and Miyazaki makes a point of stopping in at shrines around the countryside. Even the famous scene of Totoro waiting at the bus stop with the girls only comes after Mei decides she doesn’t want to wait in an Inari shrine.

At another point, when the girls are caught in a rainstorm they take shelter in a shrine dedicated to the boddhisatva Jizō (more on him below) but only after first asking permission. It’s one of the ways that Miyazaki builds the sense that the humans in the story are only one part of the natural and spiritual world around them.

One of the most striking things about this rewatch for me was that I went in remembering Totoro as a fundamentally sunny film, but in scene after scene the kids and their dad are stranded in torrential rains, or frightened by sudden, blustery winds. Nanny lectures the girls on farming techniques, and most of the neighbors spend their days working in the fields. These are people living a largely pre-industrial life, rising with the sun, working with the earth, growing and harvesting their own food, and sleeping in quiet rooms with only the sounds of frogs and crickets around them, rather than the buzz of radios or televisions. Though Miyazaki himself denies that the film is particularly religious, he did thread Shinto imagery throughout the film, and the Totoro family can be interpreted as tree spirits or kami. The tree is set off from the forest with a Torii, a traditional gateway, and wrapped in a Shimenawa—a rope used to mark a sacred area from a secular one. When Professor Kusakabe bows, he thanks the tree spirit for watching out for Mei—Totoro responds to the reverence later by rescuing her—and tells the girls about a time “when trees and people used to be friends.” Underneath that friendliness, though, is a healthy amount of awe. The children are at the mercy of Nature just as their mother is at the mercy of her illness. They are reverent toward Nature, and even when it comes in a cuddly form like a Totoro or a Catbus, it is still powerful and a little unsettling.

The only conflict comes in halfway through the film. Mrs. Kusakabe is finally well enough to come home for a weekend visit, and the girls are obviously ecstatic. They want to show their mother the new house, and tell her all about Totoro. When they get a telegram from the hospital Miyazaki again treats this through the eyes of the children. Telegrams are serious, only one family has a phone, Professor Kusakabe is at the university in the city. Each of these things build into a frightening moment for the children—has their mother relapsed? In this context it makes sense that Satsuki snaps at Mei. She’s shouldered a lot of the responsibility for her little sister, but she’s also a child missing her mom, and terrified that she’ll never see her again. So Mei, feeling completely rejected, fixates on the idea that her fresh corn will magically heal her mother and runs off to find the hospital. This goes about as well as you’d expect, and soon all the adults in the area are searching for Mei—with Nanny particularly terrified that Mei has drowned in a pond after she finds a little girl’s sandal.

Professor Kusakabe, en route to the hospital and thus unreachable in a pre-cellphone era, has no idea anything has happened to his children—he’s just rushing to his wife’s side to make sure she’s OK. Without the addition of magical Totoro this would be a horrifically tense moment. Is the children’s mother dying? Has Mei drowned? Has this family suffered two enormous losses in a single afternoon? But no, Satsuki, rather than relying on modern tech or asking an adult to take her to the hospital, falls back on her father’s respect for Nature. She calls on Totoro, who immediately helps her. Nature, rather than being a pretty background or a resource to exploit, is active, alive, and cares for the children.

Totoro was a decent hit, but it also had its share of issues coming to America. After a U.S. distributor made massive cuts to Nausicaä, Miyazaki decided that he wouldn’t allow his films to be edited for other markets. This led to two moments of cultural confusion that may have delayed the film’s arrival in America. First, the bathtub scene, where Professor, Satsuki, and Mei all soak in a tub together. According to Helen McCarthy’s study, Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation, many US companies were worried that this scene would be off-putting to American audiences, since it’s far less common for families to bathe together, particularly across gender. The other scene was a bit more innocuous. When Satsuki and Mei first explore their new home they yell and jump up and down on tatami mats. This would probably just look like kids blowing off steam to a US audience, but it’s considered a bit more disrespectful in Japan, particularly in the film’s 1950s setting. But after the issues with the U.S. edit of Nausicaa, Miyazaki refused to let anyone cut Studio Ghibli’s films. Ultimately, the first English dub was released in 1993 by Fox Video, with Disney producing a second English version in 2005.

Grave of the Fireflies, meanwhile, was distributed to the U.S. (also in 1993) through Central Park Media, and I found no evidence that anything was edited from the film in any of the releases, but the film has also never gained the cultural traction of its more family-friendly theatermate. The films were never shown together in the U.S., so while they were paired in Japanese consciousness, many U.S. anime fans don’t realize they’re connected. I think it’s is interesting though that a scene with a family bathing together was considered potentially offensive, but scenes of U.S. warplanes firing on Japanese children went unchallenged.

Are My Neighbor Totoro and Grave of the Fireflies in Conversation?

All cry/laughing aside, watching them as a double feature was a fascinating experience. Apparently when they planned the feature in Japan, they noticed that if they showed Totoro first, people would leave early on in Grave because it was too much to take after the joy of the other film. If they swapped them, Totoro could lighten the mood enough for people to experience both films. I recreated the latter experience, but what was weird was that watching Grave of the Fireflies first changed the way I saw Totoro.

First of all, the films have a lot of elements in common. Both feature a pair of young siblings—in Grave Seita is 14 and Setsuko is 4. This ten-year gap makes Seita unquestionably the adult figure to Setsuko, but he’s still too young to function as a young adult in society. His only aspiration seem to be to follow his dad into a career in the military, which the audience knows is an impossibility; Seita has no other skills, and his schooling has been interrupted by the war and their displacement. Even going in we know he can’t just find a job and raise Setsuko after the war. In Totoro Satsuki is 10, and Mei is 4. The gap isn’t so large…but, as in Grave, their parental figures are mostly absent. Their mother is in a hospital for tuberculosis, and their father, a professor, is absent-minded and clearly overwhelmed by life as a semi-single dad. Satsuki has taken over many of the domestic chores—not because her father is pushing her into the role, but because she wants to make her parents proud, and prove herself as a young adult rather than a child.

In both films the experiences are filtered entirely through the children’s point of view. Thus the young siblings trying to sing and play piano together, and capturing fireflies, despite the war raging around them; thus the utter stubbornness of a four-year-old who just wants her mom to come home from the hospital. On a more macro level, Grave portrays the destruction of Japanese cities during World War II, and how that destroys the innocence of two particular children. A decade later in Totoro, Japan has seemingly recovered from the war, and the film features lush fields and forests… but modern Japanese audiences know that this neighborhood (Miyazaki’s childhood neighborhood) has since been swallowed by Tokyo’s suburbs.

After the bleakness of Grave, I found the sweetness of Totoro both incredibly uplifting, and kind of suspect—and a bit eerie, as both films feature camphor trees, but we’ll get to that in a second.

The most heartbreaking moment of the double feature for me was the search for Mei. (Note: the following two paragraphs might ruin Totoro for you, so skip down if you need to.) Every other time I’ve watched the movie I’m emotionally invested, sure, but I know it turns out OK. After building the suspense around Mei’s disappearance, Miyazaki even includes a shot of her sitting with statues of the bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha, known in Japan as Jizō, or Ojizō-sama, who is the guardian of children (and firefighters, but that doesn’t come up here) so an audience watching this film in Japan will recognize those deities, and will know that they’re watching over Mei. It was seemingly this shot that inspired the disturbing “Totoro is actually a god of death” legend from a few years ago. In addition to watching over living children, Jizō takes care of children who die before their parents, or who are miscarried or aborted. Since they aren’t able to cross into the afterlife, they would technically be required to stack stones on the bank of the Sanzu River, um, forever, which seems harsh. Jizō takes care of them and teaches them mantras until they’ve gained enough merit to cross over, and since he’s seen protecting Mei multiple times, it added to the idea that he and Totoro were ushering one or both of the children into death. Personally I reject this theory because I hate “main character was dead/dreaming/insane/in a coma the entire time narratives”—they’re almost always lazy, and simply undercut any emotional connection that the film or book has built with its audience.

Having said that, though, investing in Totoro immediately after Grave of the Fireflies cast a shadow over how I saw the film. Here the entire community pitches in to dredge the pond when they think Mei has fallen in. When one of the farmers thanks them all for their hard work, another replies, “It could have been any one of us.” I actually started to cry again, because all I could think of was the contrast between that sentiment and the way all the adults kept their heads down and ignored Seita and Setsuko in Grave. Even worse is the next sequence, when Satsuki asks for Totoro’s help. He calls the Catbus, which seems more friendly than creepy now, and he flies through the air and rescues Mei, who is still sitting with the Jizō statues. The sisters share an ecstatic hug, and then Catbus goes the extra mile and takes them to see their mother (who is just getting over a slight cold) before taking them back to Nanny. Everything’s fine. Except this time… Mei’s rescue felt too fantastical. Even though I’ve watched this movie many, many times, and I love it, I realized that a part of me was waiting for Satsuki to wake up from a dream sequence to learn that Mei had drowned in the pond, and that the happy ending was only in her imagination. Watching Totoro this time, in the shadow of Grave of the Fireflies, changed my emotional experience. I don’t recommend it.

So about that Camphor tree…In Grave, Seita lies to Setsuko about their mother’s death for a while, hoping to give her the news in a gentle way. She finds out anyway, and he tries to soften the blow by lying again, this time telling her that their mother is buried beneath a lovely Camphor tree, and that they’ll visit her after the war. (In reality, their mother’s ashes are in a box that Seita carries with him, and seems to lose, before the film ends.) Guess what kind of tree Totoro lives in? Yeah, it’s a Camphor. And Totoro just happens to be accompanied by a middle-sized Totoro, and a small Totoro. And the small Totoro just happens to be the one that attracts Mei’s attention in the first place.

So I’ve just decided that the Grave of the Fireflies characters were all reincarnated as Totoros. Big Totoro is Mother, the Middle Totoro, always the caretaker, forever collecting acorns for Baby, is clearly Seita, and Baby Totoro is Setsuko—the one who first befriends a little girl who’s the same age she was when she died.

And if I’ve just ruined My Neighbor Totoro for you I’m sorry, but how much better is Grave of the Fireflies now? If you watch the movie believing that they all get to be Totoros in the end, you might just get through it.

The Cuddliest God of the Forest and the Legacy of Studio Ghibli

I mentioned earlier that, even with the double feature, neither film did quite as well as the studio hoped. Studio Ghibli’s success wasn’t sealed until 1990, when the board grudgingly OK’d a line of plush toys based on Totoro. These toys proved to be a goddamn tractor beam to children across Japan, and sales from the toy division kept the studio fiscally sound while Miyazaki and Takahata were able to craft new stories rather than having to churn out product. (Those toys are still a tractor beam—I cannot count how many Totoro-themed things are in my house, and I may have clapped, loudly, when he appeared onscreen during Toy Story 3.) I think I’ve made it reasonably clear on this site that I have…reservations…about capitalism. I think society’s turn toward corporatization has had a negative impact on art, childhood, farming, youth culture, the working class, the environment, individual expression, end-of-life care, and the basic ideas of what makes us human.

But…

I mean…

Even I have my weak spots.

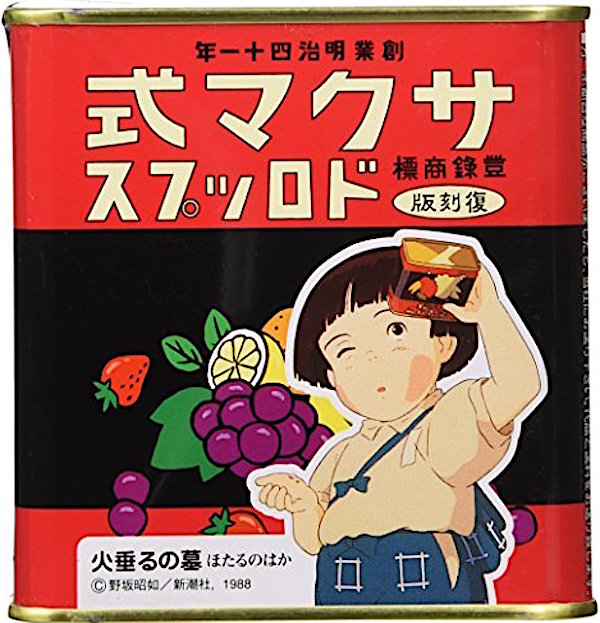

Now, perhaps you’re asking yourself “What of Grave of the Fireflies? Is there any merch I can purchase to commemorate my viewing of that classic film?” You might be shocked to learn this, but there is! Or, at least there was at one time. Both films are resolutely dedicated to presenting a child’s point of view. in Grave, Setsuko doesn’t understand a lot of what’s happening to her and her brother. She just knows that she’s hungry and scared, and responds the way a child would to any instance of being hungry and scared. Sometimes she tries to be stoic, but just as often she cries and throws tantrums that Seita, who knows the gravity of their situation, can barely tolerate. One of the saddest elements of the film is the way he carefully hoards their last symbol of life before wartime, a tin of Sakuma fruit drops.

The fruit drops have been made by the Sakuma Candy Company since 1908, and the tins, which are often released with limited edition artwork, have become collectors items. You’ve probably guess where this is going: yes, they have released Grave of the Fireflies-themed tins.

I think this is an interesting way to commemorate one of the small joys the kids have in the film, but I think I’ll stick with my Totoro plushie.

So, I made it! I rewatched Grave of the Fireflies, and while it certainly colored my viewing of Totoro, my love for the King of the Forest is undiminished. Both of these films would have been extraordinary achievements on their own, but paired they showed that Studio Ghibli, with only one feature under their collective belt, could create a range of stories from a gut-wrenching drama to one of the sweetest, most effervescent children’s movies ever made. Both films, while initially not that successful, have since been acknowledged as all-time classics of anime. Over the next thirty years, they tackled coming-of-age stories, romances, medieval epics, and fairy tales, and continued their dedication to complex female leads, environmental theme, and gorgeous animation. I can’t wait to dive into the next essay, when I discuss Studio Ghibli’s two very different coming-of-age tales: Kiki’s Delivery Service and Whisper of the Heart!

But I think I’m renewing my ban on movies about war orphans.

An earlier version of this article was published in June 2017.

Leah Schnelbach has a new life goal: night gardening with Totoro. Come follow the seeds and you will find…not an adventure, but Twitter!